The ancient Egyptian mummification process remains one of the most fascinating and sophisticated methods of body preservation in history. Developed over thousands of years, mummification was deeply tied to Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife, where preserving the body was essential for the soul’s eternal journey.

Table of Contents

What is Egyptian Mummification?

Egyptian mummification refers to the elaborate techniques used by ancient Egyptians to preserve human bodies after death. The process was deeply rooted in religious beliefs, as Egyptians believed the deceased’s soul (Ka) needed a well-preserved body to return to in the afterlife.

The practice began around 2600 BCE during the Old Kingdom and evolved over centuries, reaching its peak during the New Kingdom (1570–1070 BCE). Over time, the process became more refined, incorporating both scientific methods of preservation and spiritual rituals.

The Origins of Mummification

The origins of mummification in ancient Egypt date back to around 2600 BCE during the Old Kingdom period. Early attempts were simpler, relying on natural desiccation in the arid desert sand. Over time, the process became increasingly elaborate, incorporating embalming chemicals, intricate wrapping techniques, and burial rituals. By the New Kingdom period (1550–1070 BCE), mummification had reached its peak, becoming an art form revered across the ancient world.

Mummification Process with Pictures

To fully appreciate the intricate details of the mummification process, visual depictions help illuminate the steps involved.

What is the Mummification Process in Ancient Egypt?

Mummification in ancient Egypt involved more than just drying the body; it was a complex, multi-step process designed to prevent decay. The process could take up to 70 days and was carried out by specialized embalmers. Here’s an overview of the process:

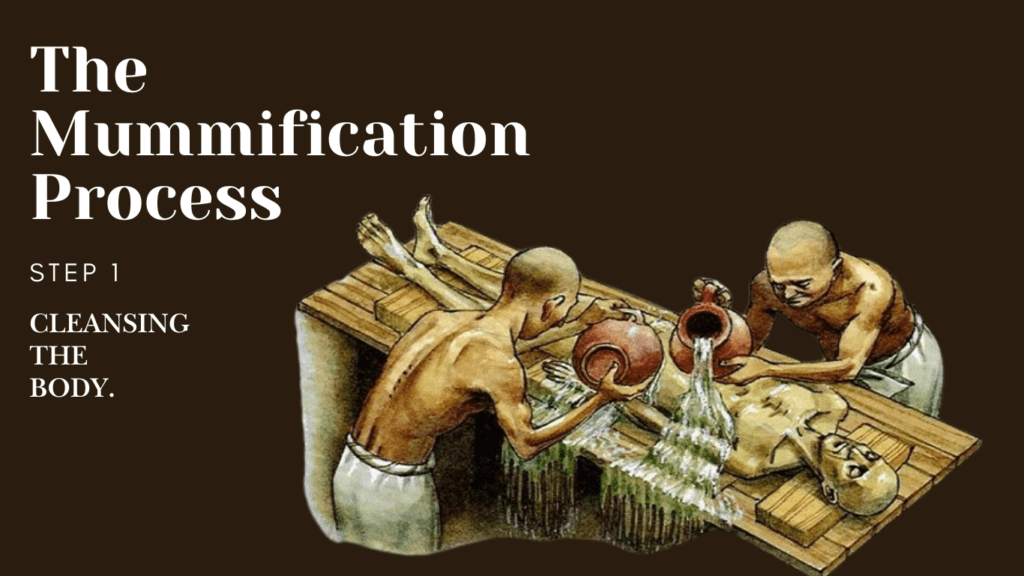

Preparation and Purification

The body was first washed with water from the Nile and ritually purified. This cleansing step symbolized renewal and spiritual preparation for the afterlife.

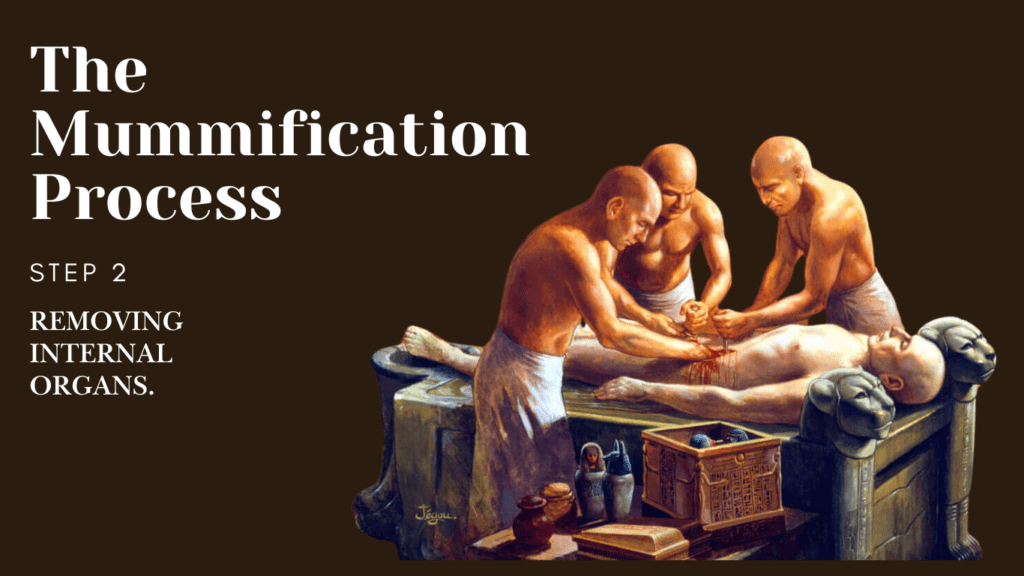

Removal of Internal Organs

Embalmers removed most internal organs to prevent decomposition. The stomach, intestines, lungs, and liver were extracted through an incision in the left side of the abdomen. These organs were dried using natron (a naturally occurring salt) and placed in canopic jars, each guarded by one of the Four Sons of Horus.

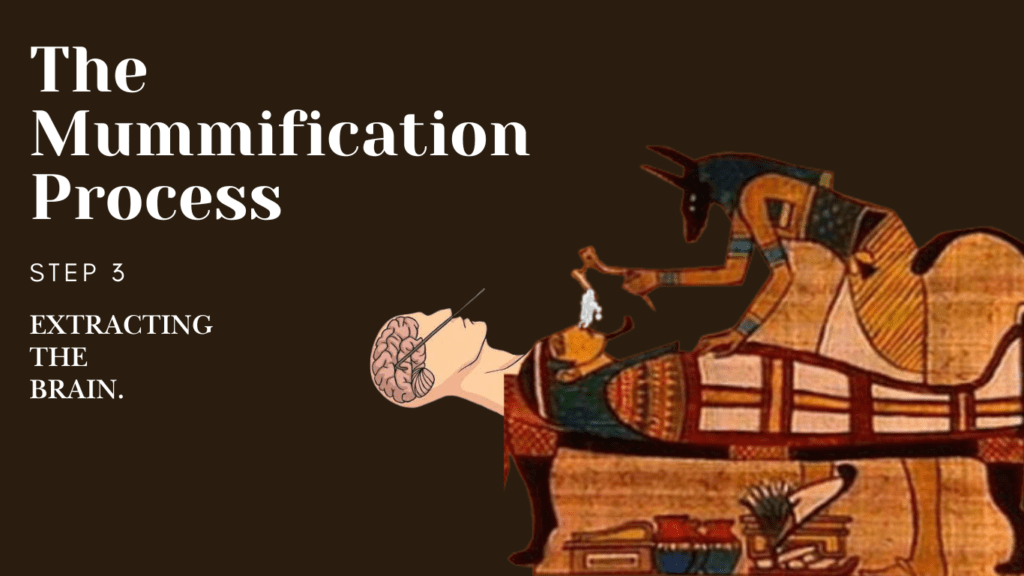

Removal of the Brain

The brain was extracted using specialized hooks inserted through the nostrils. Ancient Egyptians considered the brain unimportant, believing intelligence and emotion resided in the heart.

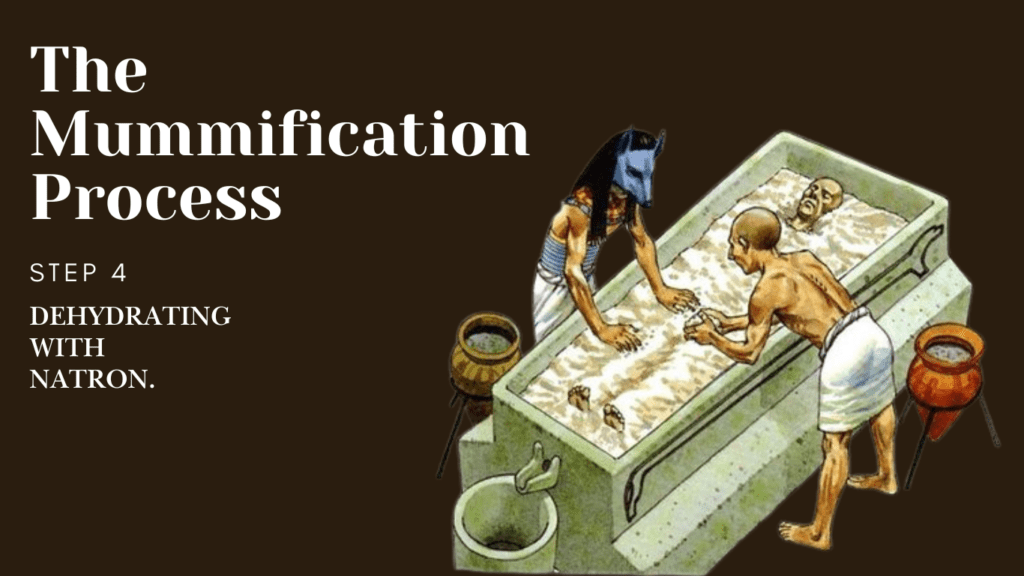

Drying the Body

The body was covered with natron to dehydrate it completely. This process took approximately 40 days and ensured the body was free of moisture, preventing decay.

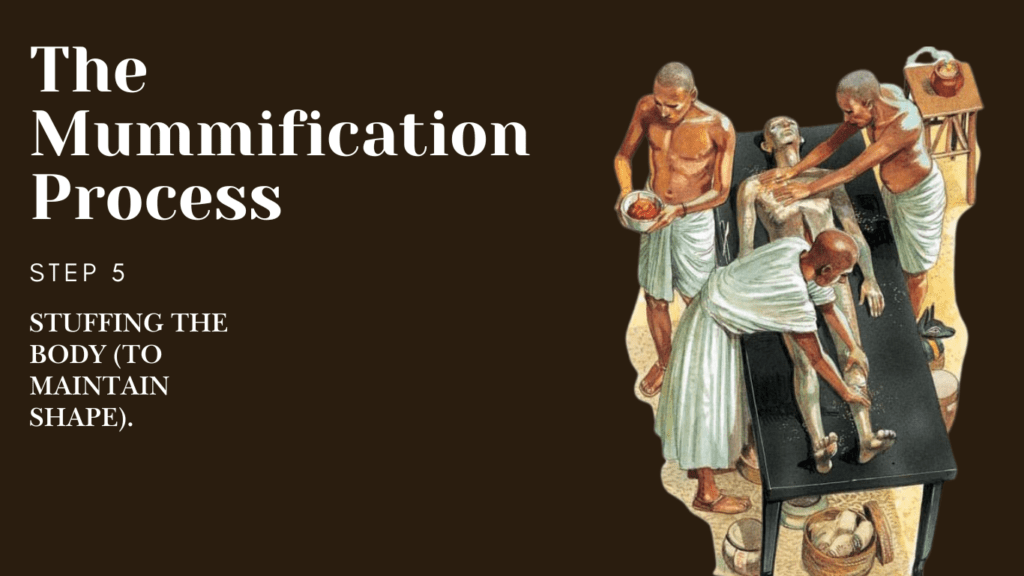

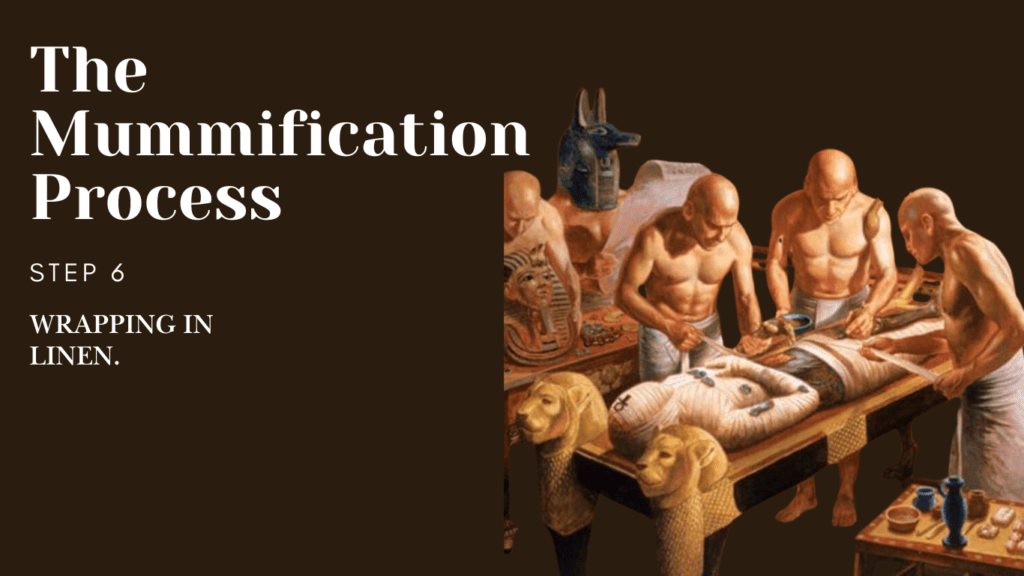

Wrapping the Body

After drying, the body was wrapped in layers of linen. Embalmers applied resin between the layers to glue them together and protect the body from moisture. Amulets were placed within the wrappings to provide protection in the afterlife.

Final Touches

The wrapped body was often adorned with a death mask, typically made of cartonnage or gold, to represent the deceased’s face. This mask was essential for the soul to recognize its body.

Placement in a Sarcophagus

The fully mummified body was placed inside a coffin or sarcophagus, often elaborately decorated with inscriptions and images to guide the deceased in the afterlife.

The History of Mummification Techniques

Initially, natural mummification occurred in the hot, dry desert sands of Egypt. Bodies buried directly in the sand were naturally desiccated due to the extreme heat and arid conditions, which halted decomposition. This accidental preservation provided the earliest inspiration for intentional mummification. Early Egyptians noticed that bodies buried in shallow pits retained their basic form and decided to replicate this phenomenon as burial practices became more elaborate.

As Egyptian society progressed, especially during the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100–2686 BCE), burials shifted from simple sand pits to constructed tombs. However, these enclosed spaces trapped moisture, leading to the rapid decay of bodies. To address this, the Egyptians began experimenting with rudimentary embalming techniques. These early attempts included wrapping the body in linen and coating it with resin or bitumen to slow decomposition. Despite their efforts, these methods were less effective than natural mummification.

By the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE), Egyptians began developing more structured embalming practices. The focus shifted to removing the internal organs, which were the primary source of decomposition. Although the methods were still relatively unsophisticated compared to later practices, this period laid the groundwork for advanced techniques.

During the Middle Kingdom (2055–1650 BCE), embalmers honed their craft significantly. The use of natron, a naturally occurring salt, became central to the preservation process. Natron was used to dehydrate the body, effectively halting bacterial growth and decomposition. This period also saw the introduction of canopic jars to store the removed internal organs, each protected by deities associated with safeguarding specific parts of the body. Additionally, embalming became more ritualized, with priests conducting ceremonies and prayers during the process to ensure the deceased’s safe passage to the afterlife.

The New Kingdom (c. 1570–1070 BCE) marked the pinnacle of mummification techniques. Embalmers mastered the art of preservation, achieving an unprecedented level of anatomical and aesthetic precision. The entire process became highly systematic, often taking up to 70 days to complete. Advanced wrapping techniques emerged, involving hundreds of yards of fine linen intricately layered around the body. Resin and oils were applied between the layers to provide additional protection against moisture and insects.

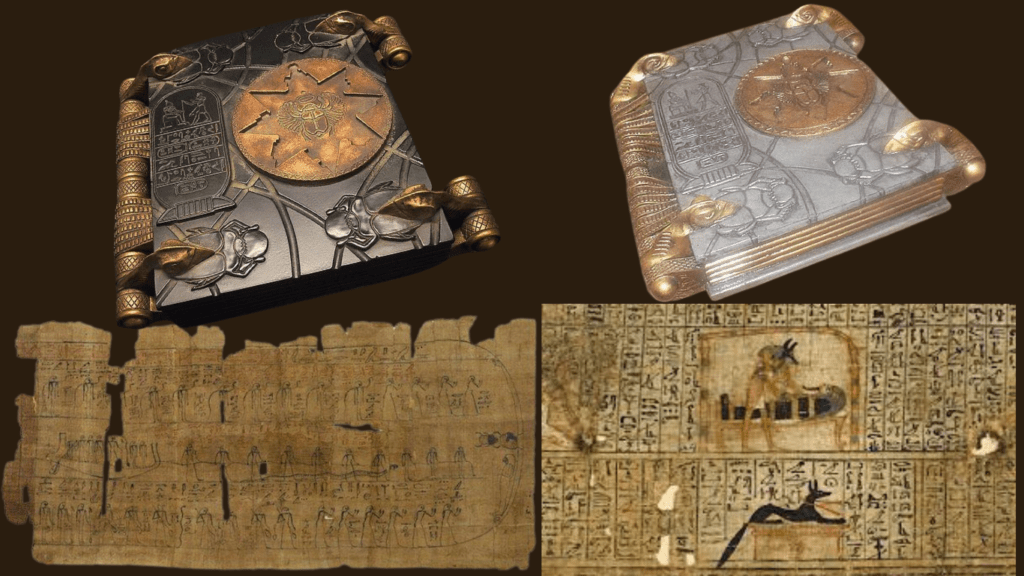

Funerary texts, such as the “Book of the Dead,” were also incorporated into the burial process during this era. These texts contained spells, instructions, and prayers designed to guide the deceased through the perilous journey to the afterlife. They were often inscribed on papyrus scrolls or tomb walls, ensuring the deceased had the necessary tools to overcome obstacles in the afterlife.

Additionally, the New Kingdom introduced the use of death masks, often crafted from cartonnage or gold, to preserve the individuality of the deceased. These masks, along with painted coffins and sarcophagi, reflected the increasing importance of personal identity and status in the afterlife. The mummification process was no longer just about preservation; it had become a deeply symbolic ritual that intertwined science, religion, and artistry.

By the Late Period (c. 664–323 BCE), mummification techniques were accessible to a wider range of social classes. Although the most elaborate methods were reserved for royalty and the elite, simpler forms of mummification were available to commoners. Innovations continued, including the use of artificial eyes and other cosmetic enhancements to give the mummified body a lifelike appearance.

The art of mummification began to decline after the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE. The spread of Christianity and changing cultural practices gradually reduced the emphasis on traditional Egyptian funerary customs. However, the legacy of these techniques endures, providing modern researchers with invaluable insights into ancient Egyptian society, beliefs, and scientific knowledge.

The Spiritual Significance of Mummification

Mummification in ancient Egypt was not merely a physical preservation of the body; it held profound spiritual significance deeply rooted in Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife. Central to this was the concept of eternal life, a cornerstone of Egyptian religion. The Egyptians believed that life continued after death, but only if the body remained intact as a vessel for the soul.

The process of mummification was intrinsically linked to their understanding of the human soul, which they divided into several components, including the “ka,” “ba,” and “akh.” The “ka” represented the vital essence or life force, while the “ba” was a unique spiritual characteristic, often depicted as a bird with a human head. The “akh” was the transfigured spirit that emerged after successful passage through the afterlife. For these elements to function harmoniously, the physical body needed to be preserved as a home for the “ka” and a point of connection for the “ba.”

Mummification was more than a physical process; it was deeply spiritual. Embalmers often recited prayers and performed rituals to ensure the deceased’s safe passage into the afterlife. The heart, left in the body or replaced by a heart scarab, was considered the seat of intelligence and judgment. During the “Weighing of the Heart” ceremony, the heart was weighed against the feather of Ma’at, symbolizing truth and justice. This ceremony was depicted in the “Book of the Dead” and served as a spiritual trial where the deceased’s moral integrity in life determined their eligibility for eternal peace. If the heart was lighter than the feather, the individual was granted access to the Field of Reeds, a paradisiacal version of their earthly existence. If heavier, the heart was devoured by Ammit, a fearsome deity, resulting in the soul’s obliteration.

The “Opening of the Mouth” ceremony was another critical ritual associated with mummification. This rite was performed to restore the deceased’s senses, allowing them to eat, drink, and speak in the afterlife. Tools resembling small chisels were used to symbolically open the mouth of the mummy or its statue, ensuring the individual’s full functionality in the next world.

Funerary texts, such as the “Pyramid Texts,” “Coffin Texts,” and the “Book of the Dead,” further illustrate the spiritual significance of mummification. These texts, often inscribed on tomb walls or written on papyrus, contained spells, hymns, and instructions to help the deceased navigate the challenges of the afterlife. The “Weighing of the Heart” ceremony, depicted in the “Book of the Dead,” highlights the belief that moral integrity in life influenced one’s fate after death. The preserved body was essential for this journey, serving as the anchor for the soul during these trials.

In addition to the body’s preservation, the inclusion of grave goods, amulets, and offerings within the tomb reflected the Egyptian desire to equip the deceased for their eternal existence. Amulets such as the scarab beetle were placed within the mummy wrappings to provide protection and ensure rebirth. Tomb paintings and carvings often depicted scenes of daily life, reinforcing the belief that the afterlife was a continuation of earthly existence.

Through mummification, the Egyptians sought to overcome death itself, achieving a state of immortality in the company of the gods. The elaborate care and reverence involved in the process underscore its profound spiritual significance, reflecting the ancient Egyptians’ deep connection to their faith and their enduring quest for eternal life.

The Legacy of Egyptian Mummification

The Egyptian mummification process reflects the ancient civilization’s unparalleled devotion to preserving life beyond death. Although the practice declined after the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, its legacy endures through preserved mummies, burial artifacts, and ancient texts.

Today, mummies continue to intrigue scientists and historians. Modern technology, such as CT scans, reveals details about their lives, health, and burial practices, offering glimpses into the rich tapestry of ancient Egyptian culture.

This detailed account of Egyptian mummification underscores its historical significance and profound cultural impact. Whether you’re fascinated by the art of preservation, ancient rituals, or the mysteries of the afterlife, the mummification process stands as a testament to human ingenuity and the enduring quest for immortality.